© Copyright Peter Crawford 2014

to view images full size open image in a new tab

'Dan was the man I always wanted to be. Digby, his batman, was the man I saw myself as.'

Frank Hampson

Frank Hampson - the Creator of Dan Dare - was born at 488 Audenshaw Road, Audenshaw, near to Manchester (now Tameside), and was educated at King George V School, a grammar school in Southport.

His brother Eric was killed in a naval action during the Second World War.

As a child, he loved to draw, and while still a pupil at George V Grammar school, he entered a drawing competition run by 'Meccano' magazine.

Not only did he win a prize for this entry, but the editor was sufficiently amused by his cartoon to ask for more.

Thus, at the age of thirteen, he received his first commission, and for the next two years his work appeared regularly in the journal.

With his School Certificate under his belt, he left school at the age of fourteen and found a job delivering telegrams for the Post Office.

The irregular hours left him with plenty of time to pursue his passion for drawing, and the official G.P.O magazine, 'The Post', soon became a regular outlet for his work.

His father, a policeman, proud of his son's talent, gathered a few of his drawings together one day and showed them to the principal of the local art school.

Between them they decided that - when he wasn't delivering telegrams - Hampson would attend the life-drawing classes there.

But it was to be another two years before he took the final plunge and abandoned his safe 'job with prospects' at the G.P.O. to become a full-time art student at the Victoria College of Arts and Science, Southport.

He was nineteen years old and the year was 1938.

The following year, shortly after the College had presented him with his National Diploma of Design (Intermediate), war broke out.

Hampson immediately volunteered for service, and during the next six years, he saw action in France and Belgium, and lived through those experiences which would inform and influence much of his future creativity.

His brother Eric was killed in a naval action during the Second World War.

It was wasn't until 1946 that he was finally discharged from the army and free to return to art college.

By then, he had risen to the rank of Lieutenant, and had married Dorothy Jackson, the daughter of a surveying engineer he'd met when taking officer training course in Wales.

The birth of a son, Peter, in 1947, meant that Hampson had to find freelance work to supplement his grant.

One of the jobs he took was to provide illustrations for 'Anvil', a Church of England magazine which had been turned from a simple 'Parish Mag' into a national publication through the entrepreneurial talents of a local parson, the Reverend Marcus Morris.

|

| Meccano |

Not only did he win a prize for this entry, but the editor was sufficiently amused by his cartoon to ask for more.

Thus, at the age of thirteen, he received his first commission, and for the next two years his work appeared regularly in the journal.

With his School Certificate under his belt, he left school at the age of fourteen and found a job delivering telegrams for the Post Office.

The irregular hours left him with plenty of time to pursue his passion for drawing, and the official G.P.O magazine, 'The Post', soon became a regular outlet for his work.

His father, a policeman, proud of his son's talent, gathered a few of his drawings together one day and showed them to the principal of the local art school.

Between them they decided that - when he wasn't delivering telegrams - Hampson would attend the life-drawing classes there.

But it was to be another two years before he took the final plunge and abandoned his safe 'job with prospects' at the G.P.O. to become a full-time art student at the Victoria College of Arts and Science, Southport.

He was nineteen years old and the year was 1938.

The following year, shortly after the College had presented him with his National Diploma of Design (Intermediate), war broke out.

Hampson immediately volunteered for service, and during the next six years, he saw action in France and Belgium, and lived through those experiences which would inform and influence much of his future creativity.

His brother Eric was killed in a naval action during the Second World War.

It was wasn't until 1946 that he was finally discharged from the army and free to return to art college.

|

| Frank and Dorothy |

The birth of a son, Peter, in 1947, meant that Hampson had to find freelance work to supplement his grant.

One of the jobs he took was to provide illustrations for 'Anvil', a Church of England magazine which had been turned from a simple 'Parish Mag' into a national publication through the entrepreneurial talents of a local parson, the Reverend Marcus Morris.

|

| Frank Hampson Drawing |

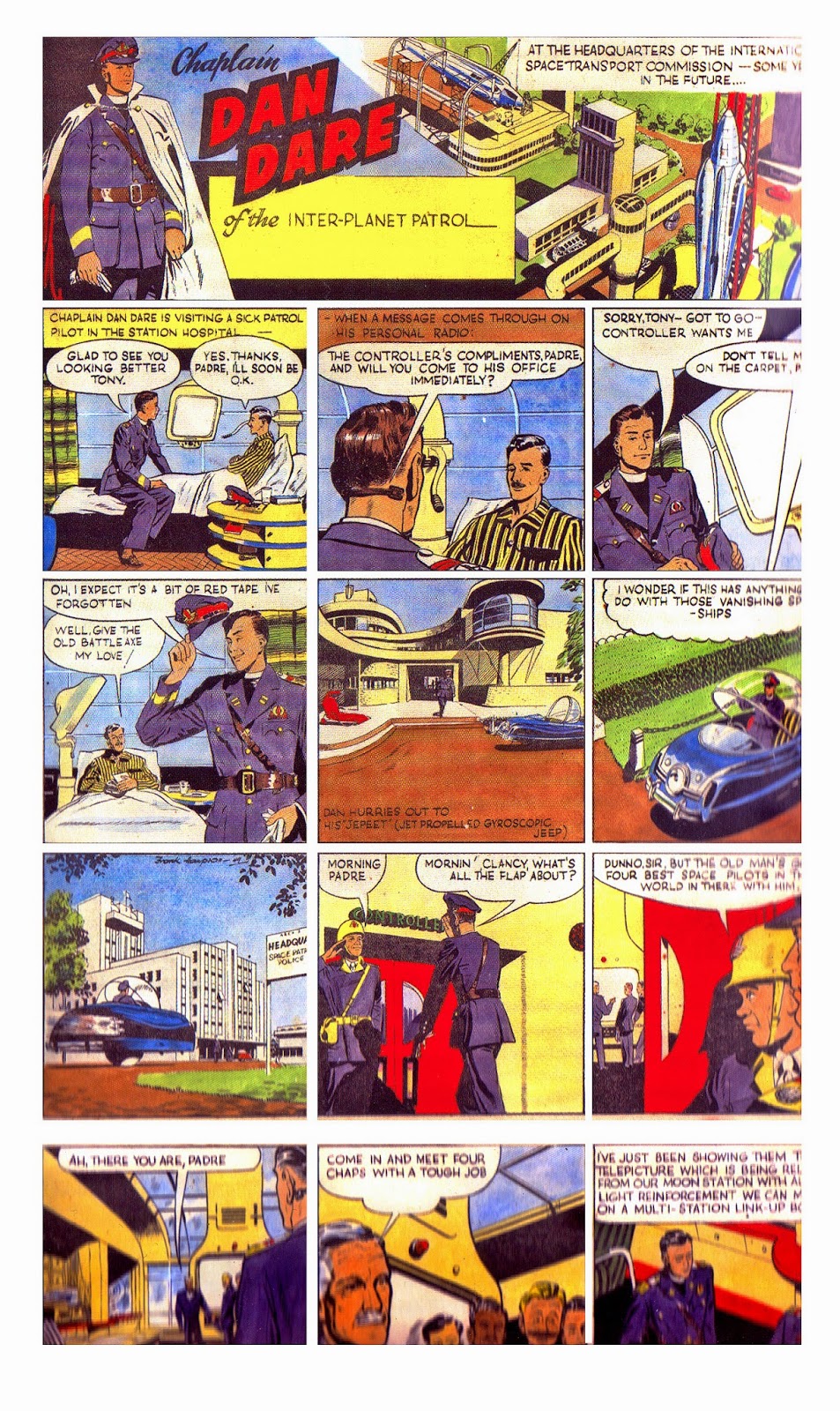

In April the following year, a revised version of the Eagle hit the bookstalls.

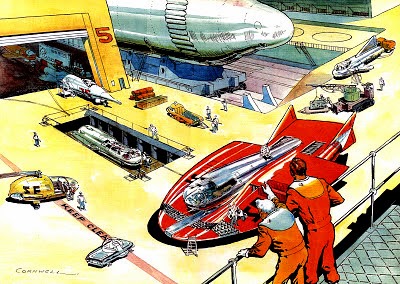

Its most popular strip was Hampson’s Dan Dare, Pilot of the Future.

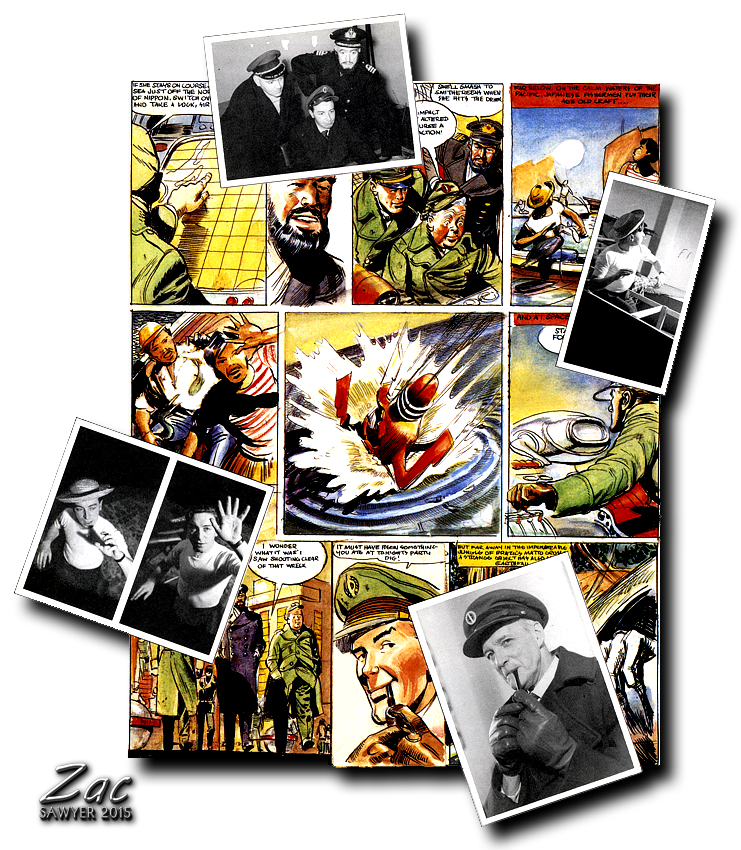

Like Alex Raymond and Milton Caniff in the U.S., Hampson instigated a studio system where, from his home in Epsom, Surrey, as many as four artists might work on two pages of the strip at any one time. When Hulton Press was bought up in 1959, and the Eagle moved to a new publisher, Hampson’s studio system was disbanded due to its cost.

|

| Evidence of Hampson's Studio System |

Hampson then began to devise seven other strip cartoon ideas, which he intended to offer to the Eagle. Partly through his own mismanagement (he told no-one what he was doing) Longacre Press accused him of breach of contract.

|

| Frank Hampson © Copyright Zac Sawyer 2015 |

The remainder of Hampson’s life was spent working as a freelance commercial artist for various publications.

Hampson was voted Prestigioso Maestro at an international convention of strip cartoon and animated film artists held at Lucca in Tuscany in 1975.

|

| Frank Hampson in Later Life |

A jury of his peers gave him a Yellow Kid Award and declared him to be the best writer and artist of strip cartoons since the end of the Second World War.

In 1978 he graduated from the Open University

He celebrated by drawing a Dan Dare strip for the University’s internal magazine.

The punch line of the script involved the University getting an application from Dare’s nemesis The Mekon.

In ailing health, sadly Frank Hampson died from a stroke, and the lingering effects of throat cancer, in July 1985, in Surrey, England.

Hampson - on his own art

"When I draw a strip cartoon I assume there will be two separate readings of any episode.

The first is when the reader scans frames and dialogue to follow the plot.

Dialogue should sound natural and flow smoothly, and everything designed so the story is clear, and quick and easy to understand.

If there’s any chance of confusion I slow the tempo, and maybe insert extra frames. Nothing should stop an even ‘read’, likely to be over in, say, two minutes.

Later (or it could be as soon as the above is finished) the reader comes to the story a second time.

Now he can study the pictorial sub plot, and enjoy looking for and finding details, inventions, concepts, ideas, artefacts and hardware, put there to add interest.

These details, often tiny, also help make venue, characters and story more authentic.

I vary picture-frames to avoid monotony, and can incorporate long, medium and close-up shots, and views from above, below and at angles.

It’s a bit like scenes in a film, which can cut from a long-distance, establishing shot, to a medium shot of the hero’s head and shoulders to a close-up of his hand reaching for the telephone.

The secret is to balance these to create maximum picture-interest.

It means, however, the artist must be able to ‘see’ the scene in his mind’s eye before he starts to draw.

When your scene is clear you can move your viewpoint round it, to as many angles as you need to tell the story.

Visualise where your characters are. If you can’t ‘see’ the venue, when you change the viewpoint your backgrounds lack conviction.

Common remedy: have no backgrounds at all.

Finally there is a parallel with writing.

The well-known author and critic Sir Arthur Quiller Couch said: ‘Whenever you feel an impulse to perpetrate a piece of exceptionally fine writing, obey it—whole-heartedly—and delete it before sending your manuscript to press. Murder your darlings.’

I believe, most emphatically, that every picture should be drawn from life.

But if a choice has to be made between including some particularly nice piece of drawing, and keeping the story clear, then the drawing should be sacrificed."

Hampson started drawing the way he meant to continue.

THE 'BAKE-HOUSE STUDIO'

Hampson - on his own art

"When I draw a strip cartoon I assume there will be two separate readings of any episode.

The first is when the reader scans frames and dialogue to follow the plot.

Dialogue should sound natural and flow smoothly, and everything designed so the story is clear, and quick and easy to understand.

If there’s any chance of confusion I slow the tempo, and maybe insert extra frames. Nothing should stop an even ‘read’, likely to be over in, say, two minutes.

Later (or it could be as soon as the above is finished) the reader comes to the story a second time.

Now he can study the pictorial sub plot, and enjoy looking for and finding details, inventions, concepts, ideas, artefacts and hardware, put there to add interest.

These details, often tiny, also help make venue, characters and story more authentic.

I vary picture-frames to avoid monotony, and can incorporate long, medium and close-up shots, and views from above, below and at angles.

It’s a bit like scenes in a film, which can cut from a long-distance, establishing shot, to a medium shot of the hero’s head and shoulders to a close-up of his hand reaching for the telephone.

The secret is to balance these to create maximum picture-interest.

It means, however, the artist must be able to ‘see’ the scene in his mind’s eye before he starts to draw.

When your scene is clear you can move your viewpoint round it, to as many angles as you need to tell the story.

Visualise where your characters are. If you can’t ‘see’ the venue, when you change the viewpoint your backgrounds lack conviction.

Common remedy: have no backgrounds at all.

Finally there is a parallel with writing.

The well-known author and critic Sir Arthur Quiller Couch said: ‘Whenever you feel an impulse to perpetrate a piece of exceptionally fine writing, obey it—whole-heartedly—and delete it before sending your manuscript to press. Murder your darlings.’

I believe, most emphatically, that every picture should be drawn from life.

But if a choice has to be made between including some particularly nice piece of drawing, and keeping the story clear, then the drawing should be sacrificed."

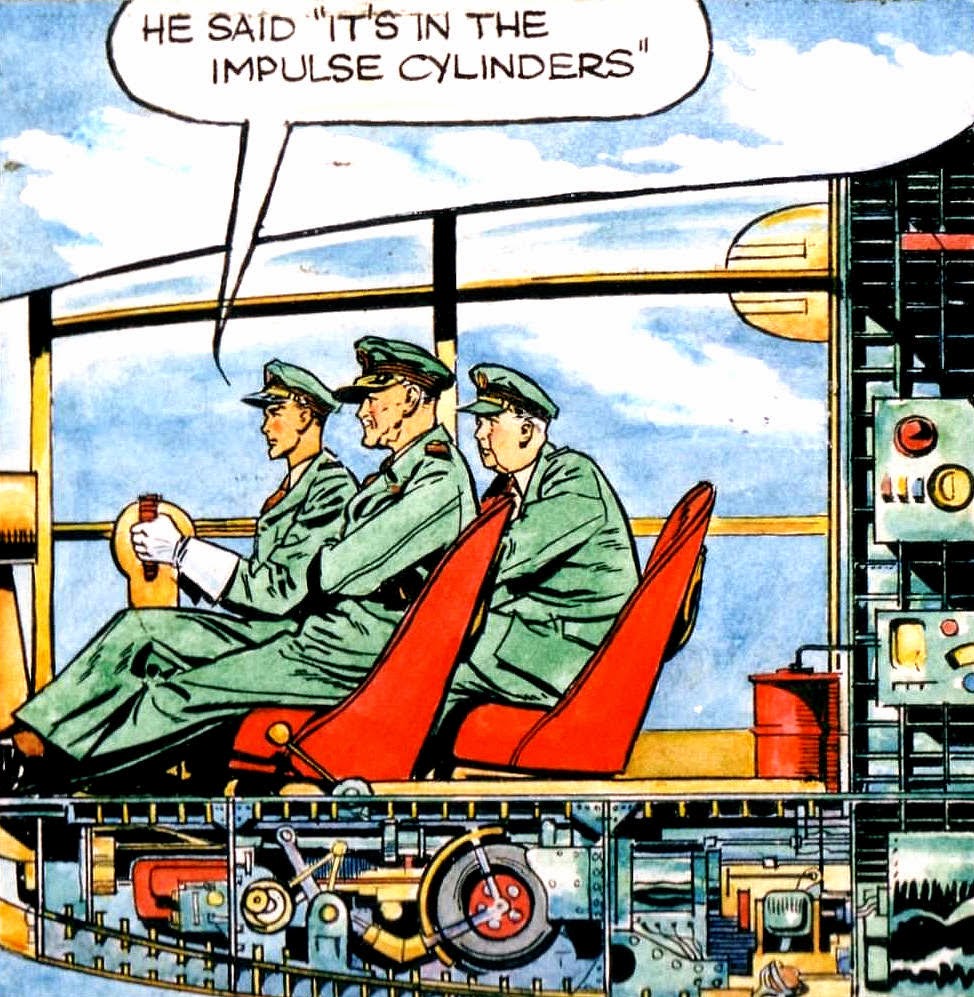

JET-COPTER CUTAWAY

HAMPSON 's OBSESSION WITH DETAIL

|

| to view image full size open image in a new tab |

This frame is from Eagle No. 4 and was printed only 3.15" deep by 3" wide - yet we see the innards of his jet-copter down to the rivets in the corner-plates.

Was this necessary ?

Of course not. So why did he do it ?

Because he could, and because he loved to work like this.

Was it good for him ?

On the contrary; within 18 months he became ill from overwork.

THE 'BAKE-HOUSE STUDIO'

At the beginning of the 'Venus Story' Hampson had begun assembling his studio.

Harold Johns, Hampson’s contemporary and close friend from Southport Art College, was an obvious first choice, and quiet, almost secretive advertisements in trade papers brought in young, enthusiastic artists who were fascinated by Hampson and his plans and wanted to work with him: Jocelyn Thomas and Joan Humphries (later Porter), Greta Tomlinson (who would form a very fruitful partnership with Johns) and Canadian Bruce Sterling, a much more experienced contemporary of Hampson, and the first to leave after suggesting that the punishing hours and conditions were not necessary.

With a team, a studio was required, and the most unlikely of sites was found on Botanic Road, Southport.

It was called the Bake-house, and it was a brick-built lean-to and former bakery that nevertheless offered two large overhead windows, a third in one end wall and fanlight windows along its length.

It was cold and cramped – and everyone hated it.

But it was home to Frank Hampson’s studio, and that meant not only 'Dan Dare' but 'The Great Adventurer' (the life of St Paul), 'Rob Conway' (an undistinguished strip about an air cadet joining the search for a Himalayan secret city) and 'Tommy Walls', a full-page advert for Wall’s Ice Cream in comic strip fashion.

And in this tiny place, a team of seven people worked longer hours than Victorian factory hands to fulfill Frank Hampson's vision.

Each weekend Hampson – who was writing the story as well as drawing it – worked alone on two full-color ‘rough’ pages, drawn in high detail, fully-colored, and not far from being finished.

Then two days were devoted to the team posing, photographing and developing each scene, leaving only three days in which to create that week’s art.

Hampson would usually take the first page, it being Eagle‘s cover, and his studio would divide the panels of page two between them.

It was not merely a case of drawing individual panels and sticking these down, whilst disciplining one’s natural talent into channeling what Hampson wanted into the realism he demanded.

Some original pages are little short of a jigsaw puzzle, with cut-out space ships pasted onto Space-fleet backgrounds, and figures pasted over scenes.

It was cumbersome, it was awkward, and it was draining.

It took hours, - long draining hours, - frequently working (unpaid) extra hours until the birds woke up in the morning.

And that was when Frank Hampson didn’t have another, better idea that would cause days of work to be thrown out.

Bruce Sterling, older than his colleagues, an established professional, thought it unnecessary.

Given his background, he was also prepared to stand up to Hampson in arguments about art where the junior artists, in their first jobs in an era where the prevailing anticipation was of jobs being for life, were not willing to do so.

And so Sterling left, and Eric Eden, another of Hampson’s friends from Southport Art College, although in a junior year, joined the team.

Eden would go on to a long involvement with Dan Dare, stretching way beyond Hampson’s departure in 1959, and would become the studio’s master with the airbrush, in which role he would eventually specialize.

The Bakehouse lasted less than eight months.

It was inadequate from the start, and Hampson had already started looking for better.

Hultons wanted Marcus Morris in London, rather than commuting from Southport and, since so much money was going into it, it was better to have Hampson’s studio closer to ‘home’ as well.

At first, they had to share 'The Firs', in Epsom, with Morris and his actress wife, Jessica Fanning, who did not like the thought of so many strangers in her home, but eventually Hampson and his wife Dorothy bought Bayford Lodge, and transferred a by then much streamlined studio to there.

Why did Hampson’s assistants put up with what were extremely cruel and stressful working conditions that would horrify anyone trying to keep up with that today ?

In part it was because they were young, a decade junior to Frank Hampson, who was, let’s not forget, a War veteran.

This was the Fifties, and not even deep enough into the Fifties for it to have taken shape as a different decade.

The War was not a decade behind, food rationing still existed when 'Eagle' was born, and you did not question your boss.

But there were two other considerations that, given all the comments made in later life by those who worked with Frank Hampson, seem, to me, to be more powerful.

The first is that not only did Frank Hampson never ask any of his studio to do something he was not prepared to do, he committed more, far, - far more, - in terms of intensity, in terms of effort, in terms of sheer time even than they did.

Whilst some would argue whether it was all necessary, no-one ever suggested that their boss did not do even more than he asked them to do.

And every one of them were absolutely fascinated by Frank Hampson’s work.

They had a ringside seat at the creation of something that, with the greatest possible respect, was beyond them, and everybody wanted to see it happen.

As Don Harley, the future ‘second best Dan Dare artist in the world’, always said, Hampson’s own pure unadulterated work needed only finishing to be complete, and in Harley’s eyes contained a freshness that the eventual art lacked, but Keith Watson, who would restore Hampson’s look to a feature that resisted being killed, pointed to what was published, and regards that as all the justification ever needed for Hampson’s complex, unwieldy approach.

And in 2014, we’re still talking about a weekly comic story created for young boys.

What more proof do we need that Frank Hampson did something spectacularly right.

'THE FIRS' STUDIO

For the first eight months of the series, Frank Hampson and his team produced 'Dan Dare' in the constricted confines of the 'Bakehouse' in Southport.

Eagle’s editor, the Reverend Marcus Morris, continued to hold his living at Ainsdale, and to conduct services as often as his editorial duties made possible (?).

But Eagle‘s circulation, settling in at around three quarters of a million copies every week, made it of great importance to Hulton Press, and thus made its editor’s availability in London a thing of importance to them.

Also, given that Dan Dare was the most important element of Eagle, and the amount of money being invested weekly into Frank Hampson and his unique studio, it was of equal importance to bring the whole studio much closer to home.

The destination was Epsom, in Surrey, home to the Derby, and only twenty miles outside of London.

The Morrises moved into a spacious house, 'The Firs', as a home, and the Hampson studio moved in right after them, into a private home, bringing the entire team, and the already burgeoning reference materials that Hampson accumulated, whch was fundamental to the consistency and realism of the art.

It was not an easy mix.

Remember too that Hampson’s approach to the strip involved two days a week of shooting and developing multiple photographs, as each panel of the colour rough was staged, with multiple photos frequently required for a single scene, as each element of the same might need to be separately defined.

Add to this that the studio still consisted of half a dozen people, working the same extremely long, unsociable hours, often making cups of tea in the family kitchen, and it was a recipe for conflict. Hampson’s assistants did not live at the Firs, but they still spent far more time there than they did at their scattered lodgings.

And the move to Epsom brought in another member of the studio in Don Harley.

Harley was at College locally, and had trained under Sir Stanley Spencer, but he had been immensely impressed by Hampson and his work, and when he qualified, he approached Hampson and was taken on board.

Within a few years, Hampson would be describing him as ‘the second best Dan Dare artist in the world’, and would be co-signing Harley’s name, together with his own, to the Dan Dare series.

As one man entered, another departed.

The pace was punishing, so much so that Hampson fell ill during the last month of ‘The Venus Story’, and was forced to take four weeks off.

Everyone was exhausted.

Don Harley would leave at tea-time to go home and eat, but rarely escaped without Hampson catching him, and seeking reassurances that Harley would be back: not tomorrow, but later that evening. Sometimes there were telegrams, asking why he wasn’t back yet.

Everyone was unhappy, and Eric Eden voiced the team’s concerns to Hampson.

Was this punishing schedule really necessary - and were the hours not too much ?

Hampson was angered.

Eden was his 'friend' from Southport Art College (did Hampson really have any friends ?).

He’d come aboard to replace Bruce Sterling, had moved to the other end of the country.

But Hampson thought that this was unacceptable, and was insurrection.

Was he the ringleader for a mass rebellion ?

Eden was sacked, abruptly.

His replacement was, ironically, Bruce Sterling.

Sterling lived earby in Ruislip and was persuaded to return on promises that things had changed, that the workload wasn’t as insane as before.

It was, however, and so Sterling moved on again.

And there were other departures, but by then the studio had moved again.

It really wasn’t a good fit in 'the Firs'.

Morris’s wife, the actress Jessica Fanning, was very unhappy at having all these artists hanging around her house.

They were, after all, mere employees, underlings, lucky to have a job, but insufficiently grateful to her husband for that.

Hultons bit the bullet.

They bought Bayford Lodge, also in Epsom, as a home for the Hampsons, and a studio for the strip and the team.

Here the Hampson studio would stay for the remainder of Frank Hampson’s tenure on his creation. But it still would not be entirely peaceful.

'BAYFORD LODGE' STUDIO

The set-up at The Firs was impossible. It suited no-one except Hultons, who had their Editor and Art Director/chief draw close to London, but for everyone else it was a disaster that could only get worse.

So Hulton Press accepted the need to establish Frank Hampson’s studio elsewhere in Epsom, this time at Bayford Lodge, a large, detached home that would double as a home for Frank, Dorothy and Peter, whilst providing ample space for the team to work. Not just studio space, for artists and for the ever-burgeoning reference section, but room for the exacting business of posing for photos, taking and developing film that underlay the increasingly rich and detailed art of the studio.

Hampson even had a bedroom floor removed to enable overhead and steeply angled shots to be taken.

All in service of a series that he was determined would get ever better.

Frank Hampson had ambitions for Dan Dare: breaking into the American newspaper market, for instance, and beyond that the dream of animation, for which his patient, labour intensive studio of assistants would be the foundation.

But Hulton Press completely lacked Hampson’s vision for the possibilities inherent in the series, which would, in turn, lead to frustration and grief.

In the meantime, the work went on.

Increasingly, it went on without direct contributions from Harold Johns and Greta Tomlinson.

Even at Bayford Lodge, space was not infinite, and the pair would themselves working from, first, home, and then studios rented by the two to enable them to continue.

Out of sight seems to imply out of mind: Johns and Tomlinson had less and less to do, and they had an offer for outside work that would both occupy that extra capacity but also give them an additional income.

Ever-loyal, Johns went to Marcus Morris on behalf of himself and Greta, to seek permission.

This was given, although on the strict condition that Johns and Tomlinson’s first duties had to be to Frank Hampson and Dan Dare, to the extent of setting aside other jobs (and contracts) to work for Hulton.

The duo agreed and started on their new venture, but it did not sit well with Hampson, who saw it as the rankest treachery.

All considerations of 'friendship' with Johns were forgotten.

Within a few weeks, Johns was summoned to London to meet Morris.

Tomlinson traveled with him, taking advantage of the break to visit the shops: thirty minutes after leaving Johns at Hulton, she was shocked at his catching up to her with the news that they had both been sacked.

Neither worked for Frank Hampson again.

But the pantomime continued.

Eric Eden had tried to debate the workload and had been sacked as the putative head of a conspiracy.

Now Hampson wrote to invite him back: there had been a conspiracy but Eden hadn't been involved.

So Eden returned for his third stint on Dan Dare.

For the most part, that left the Hampson studio in a settled state until the end of the decade.

Hampson was in control, with Don Harley as his principal assistant – and during 'The Man from Nowhere' Harley’s contribution was so important that Hampson, off his own bat, began to co-sign his chief assistant’s name to the strip.

Joan Humphries managed the Studio, Eric Eden was the airbrush specialist.

Other artists would come and go, in junior roles, but these would be the Frank Hampson studio long-termers at Bayford Lodge, until Keith Watson joined the studio in 1958.

There were still choppy waters ahead, times when Hampson sought to reduce, even eliminate his own drawing contributions in favor of a role directing those who worked under him, times when Desmond Walduck would return to help out, but 'Bayford Lodge' would be the safe and stable home to all henceforth, and it would remain Frank and Dorothy’s family home long after Frank was forcibly separated from his creation.

Eagle’s editor, the Reverend Marcus Morris, continued to hold his living at Ainsdale, and to conduct services as often as his editorial duties made possible (?).

But Eagle‘s circulation, settling in at around three quarters of a million copies every week, made it of great importance to Hulton Press, and thus made its editor’s availability in London a thing of importance to them.

Also, given that Dan Dare was the most important element of Eagle, and the amount of money being invested weekly into Frank Hampson and his unique studio, it was of equal importance to bring the whole studio much closer to home.

The destination was Epsom, in Surrey, home to the Derby, and only twenty miles outside of London.

The Morrises moved into a spacious house, 'The Firs', as a home, and the Hampson studio moved in right after them, into a private home, bringing the entire team, and the already burgeoning reference materials that Hampson accumulated, whch was fundamental to the consistency and realism of the art.

It was not an easy mix.

Remember too that Hampson’s approach to the strip involved two days a week of shooting and developing multiple photographs, as each panel of the colour rough was staged, with multiple photos frequently required for a single scene, as each element of the same might need to be separately defined.

Add to this that the studio still consisted of half a dozen people, working the same extremely long, unsociable hours, often making cups of tea in the family kitchen, and it was a recipe for conflict. Hampson’s assistants did not live at the Firs, but they still spent far more time there than they did at their scattered lodgings.

And the move to Epsom brought in another member of the studio in Don Harley.

Harley was at College locally, and had trained under Sir Stanley Spencer, but he had been immensely impressed by Hampson and his work, and when he qualified, he approached Hampson and was taken on board.

Within a few years, Hampson would be describing him as ‘the second best Dan Dare artist in the world’, and would be co-signing Harley’s name, together with his own, to the Dan Dare series.

As one man entered, another departed.

The pace was punishing, so much so that Hampson fell ill during the last month of ‘The Venus Story’, and was forced to take four weeks off.

Everyone was exhausted.

Don Harley would leave at tea-time to go home and eat, but rarely escaped without Hampson catching him, and seeking reassurances that Harley would be back: not tomorrow, but later that evening. Sometimes there were telegrams, asking why he wasn’t back yet.

Everyone was unhappy, and Eric Eden voiced the team’s concerns to Hampson.

Was this punishing schedule really necessary - and were the hours not too much ?

Hampson was angered.

Eden was his 'friend' from Southport Art College (did Hampson really have any friends ?).

He’d come aboard to replace Bruce Sterling, had moved to the other end of the country.

But Hampson thought that this was unacceptable, and was insurrection.

Was he the ringleader for a mass rebellion ?

Eden was sacked, abruptly.

His replacement was, ironically, Bruce Sterling.

Sterling lived earby in Ruislip and was persuaded to return on promises that things had changed, that the workload wasn’t as insane as before.

It was, however, and so Sterling moved on again.

And there were other departures, but by then the studio had moved again.

It really wasn’t a good fit in 'the Firs'.

Morris’s wife, the actress Jessica Fanning, was very unhappy at having all these artists hanging around her house.

They were, after all, mere employees, underlings, lucky to have a job, but insufficiently grateful to her husband for that.

Hultons bit the bullet.

They bought Bayford Lodge, also in Epsom, as a home for the Hampsons, and a studio for the strip and the team.

Here the Hampson studio would stay for the remainder of Frank Hampson’s tenure on his creation. But it still would not be entirely peaceful.

'BAYFORD LODGE' STUDIO

The set-up at The Firs was impossible. It suited no-one except Hultons, who had their Editor and Art Director/chief draw close to London, but for everyone else it was a disaster that could only get worse.

So Hulton Press accepted the need to establish Frank Hampson’s studio elsewhere in Epsom, this time at Bayford Lodge, a large, detached home that would double as a home for Frank, Dorothy and Peter, whilst providing ample space for the team to work. Not just studio space, for artists and for the ever-burgeoning reference section, but room for the exacting business of posing for photos, taking and developing film that underlay the increasingly rich and detailed art of the studio.

Hampson even had a bedroom floor removed to enable overhead and steeply angled shots to be taken.

All in service of a series that he was determined would get ever better.

Frank Hampson had ambitions for Dan Dare: breaking into the American newspaper market, for instance, and beyond that the dream of animation, for which his patient, labour intensive studio of assistants would be the foundation.

But Hulton Press completely lacked Hampson’s vision for the possibilities inherent in the series, which would, in turn, lead to frustration and grief.

In the meantime, the work went on.

Increasingly, it went on without direct contributions from Harold Johns and Greta Tomlinson.

Even at Bayford Lodge, space was not infinite, and the pair would themselves working from, first, home, and then studios rented by the two to enable them to continue.

Out of sight seems to imply out of mind: Johns and Tomlinson had less and less to do, and they had an offer for outside work that would both occupy that extra capacity but also give them an additional income.

Ever-loyal, Johns went to Marcus Morris on behalf of himself and Greta, to seek permission.

This was given, although on the strict condition that Johns and Tomlinson’s first duties had to be to Frank Hampson and Dan Dare, to the extent of setting aside other jobs (and contracts) to work for Hulton.

The duo agreed and started on their new venture, but it did not sit well with Hampson, who saw it as the rankest treachery.

All considerations of 'friendship' with Johns were forgotten.

Within a few weeks, Johns was summoned to London to meet Morris.

Tomlinson traveled with him, taking advantage of the break to visit the shops: thirty minutes after leaving Johns at Hulton, she was shocked at his catching up to her with the news that they had both been sacked.

Neither worked for Frank Hampson again.

But the pantomime continued.

Eric Eden had tried to debate the workload and had been sacked as the putative head of a conspiracy.

Now Hampson wrote to invite him back: there had been a conspiracy but Eden hadn't been involved.

So Eden returned for his third stint on Dan Dare.

For the most part, that left the Hampson studio in a settled state until the end of the decade.

Hampson was in control, with Don Harley as his principal assistant – and during 'The Man from Nowhere' Harley’s contribution was so important that Hampson, off his own bat, began to co-sign his chief assistant’s name to the strip.

Joan Humphries managed the Studio, Eric Eden was the airbrush specialist.

Other artists would come and go, in junior roles, but these would be the Frank Hampson studio long-termers at Bayford Lodge, until Keith Watson joined the studio in 1958.

There were still choppy waters ahead, times when Hampson sought to reduce, even eliminate his own drawing contributions in favor of a role directing those who worked under him, times when Desmond Walduck would return to help out, but 'Bayford Lodge' would be the safe and stable home to all henceforth, and it would remain Frank and Dorothy’s family home long after Frank was forcibly separated from his creation.

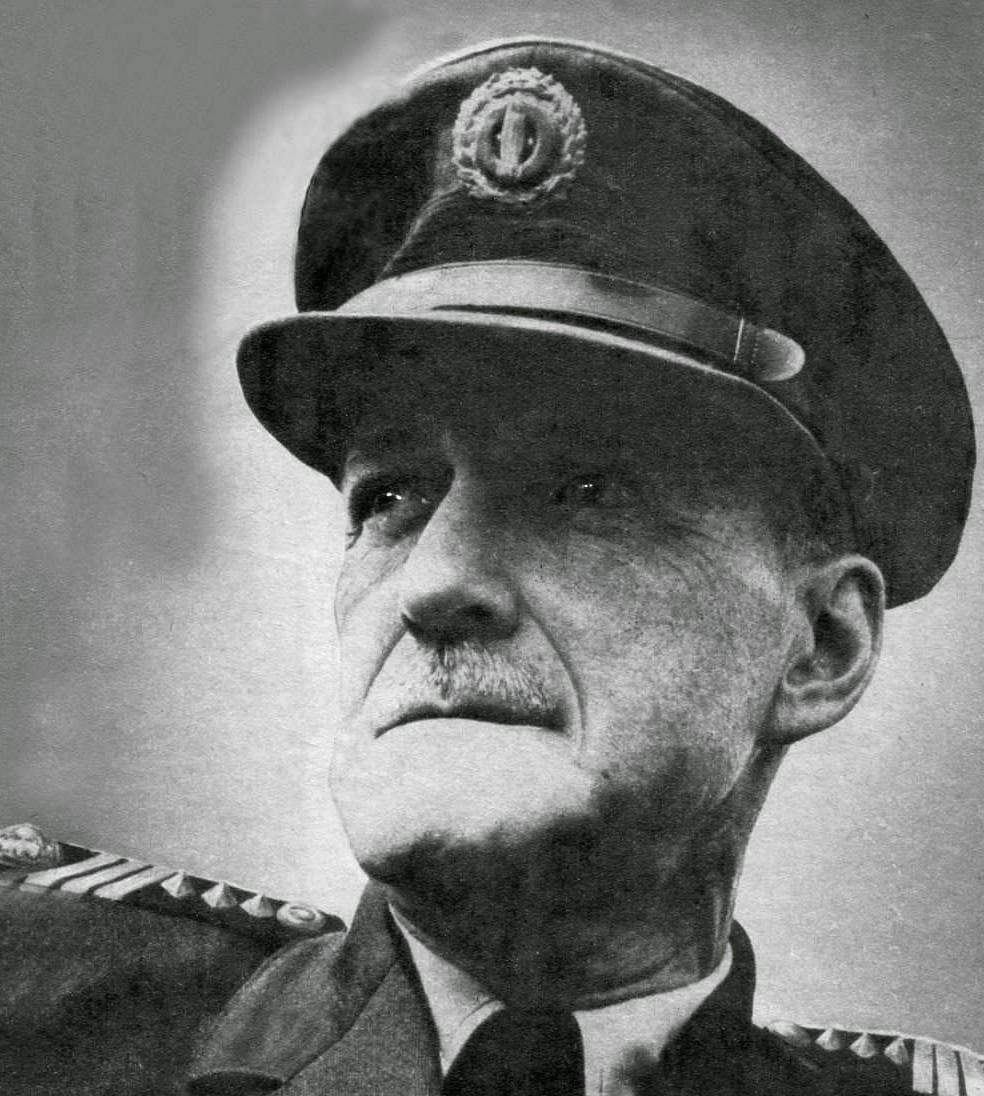

'Pop' Hampson

|

| 'Pop' Hampson |

|

| Sir Hubert Guest |

He was no artist, but was rather a retired policeman.

Not only did he make the tea, do also sorts of little jobs and chores, but rther more importantly he was the model for one of the key characters in the stories - Sir Hubert Guest, the Controller of the Space Fleet, and Dan Dare's boss.

Harold Johns

|

| Original Dummy Issue of the 'Eagle' |

|

| Harold Johns |

Harold Alfred Johns was born on 14 June 1918 and studied at Victoria College of Art and Science in 1938, where he met Frank Hampson.

During the Second World War Harold drove tanks in the Yorkshire Hussars, - later trained as a cartographer, and was eventually awarded the British Empire Medal.

After the war, he studied at Southport School of Arts and Crafts, again with Hampson.

He assisted Hampson and Marcus Morris in producing the original dummy issue of the 'Eagle' that sold the paper to Hulton Press, and soon joined Hampson's studio to work on Dan Dare.

When Frank Hampson fell ill, in the summer of 1952, Johns took over as the primary artist for the current story, "Marooned on Mercury", and he was assisted by Greta Tomlinson, from scripts written by Chad Varah.

|

| From left to right, Frank Hampson, Joan Porter, Greta Tomlinson, Robert Hampson, Harold Johns and Eric Eden |

Harold continued to work as an illustrator, until he died quite uddenly, collapsing on leaving his car, whilst out sketching in Sefton, Lancashire, in 1980, at the early age 62.

As a comic strip artist he was nearly as good as Frank, and much of his work is almost indistinguishable from that of Hampson at his best.

As a comic strip artist he was nearly as good as Frank, and much of his work is almost indistinguishable from that of Hampson at his best.

|

| Greta Tomlinson from 'So Long Ago So Clear' |

|

| Greta Tomlinson |

Greta Tomlinson was born in Burnley, Lancashire, and studied at the Slade School of Fine Art, graduating in 1949.

She specialised in the figure, and took her portfolio around various studios and fashion houses, before replying to an ad in the Advertisers Journal which turned out to be for the Eagle comic, then in development.

She joined Frank Hampson's studio, working on "Dan Dare, initially to draw figures which Hampson would then work on to produce the characters, but this process took too long, and later photo reference was used instead.

Most significantly, Greta was the model for the character 'Professor Peabody'.

When Hampson fell ill in the summer of 1952, she and Harold Johns produced the art for the "Marooned on Mercury" story, from scripts which had been written by Chad Varah.

She and Johns were subsequently sacked, in 1953, for moonlighting on other comics, despite having previously cleared it with Marcus Morris, the Eagle's editor.

Greta was, according to Frank Hampson, the model and inspiration for Professor Peabody.

She later worked in fashion, advertising and television, before marrying and moving to Iraq, where she became the local rep for the Elizabeth Arden cosmetics company.

She and her husband returned to England in 1969.

She still paints and draws, and has been exhibited in many galleries.

Eric Eden

Eric Lewis Eden was born in Lewisham, London, on 22 November 1924.

He was a land worker during the Second World War, and afterwards studied at Southport School of Art with Frank Hampson.

He joined Hampson's studio working on 'Dan Dare' for the 'Eagle', specializing in airbrush work.

He was sacked during the second story-line for objecting to the long work hours Hampson demanded, and worked in advertising for a couple of years before returning in 1955, and worked for Hampson alongside Don Harley and Joan Porter, until the studio was disbanded in 1959, after Odhams Press took over the paper.

After that he wrote scripts for the strip, with the infamous Frank Bellamy and Don Harley drawing for the first year, and Don Harley and Bruce Cornwell after that.

He finally left in 1962 and returned to drawing at TV21, working on "Lady Penelope", "XL5" and "The Daleks" among other strips.

He died at his home in Clun, Shropshire, in 1983, aged only 59.

Don Harley

Donald Eric Harley was born in London in 1927, and studied at Epsom College of Art, where Frank Hampson visited to give a talk about the 'Eagle' and 'Dan Dare'

Arthur Bruce Cornwell was the son of Arthur Redfern Cornwell, an English architect and draughts-man, and his Scottish wife Margaret C. Cornwell.

She specialised in the figure, and took her portfolio around various studios and fashion houses, before replying to an ad in the Advertisers Journal which turned out to be for the Eagle comic, then in development.

She joined Frank Hampson's studio, working on "Dan Dare, initially to draw figures which Hampson would then work on to produce the characters, but this process took too long, and later photo reference was used instead.

Most significantly, Greta was the model for the character 'Professor Peabody'.

|

| Professor Peabody |

She and Johns were subsequently sacked, in 1953, for moonlighting on other comics, despite having previously cleared it with Marcus Morris, the Eagle's editor.

Greta was, according to Frank Hampson, the model and inspiration for Professor Peabody.

She later worked in fashion, advertising and television, before marrying and moving to Iraq, where she became the local rep for the Elizabeth Arden cosmetics company.

She and her husband returned to England in 1969.

She still paints and draws, and has been exhibited in many galleries.

Eric Eden

|

| Eric Eden and Don Harley |

|

| Eric Eden as Lex O'Malley |

He was a land worker during the Second World War, and afterwards studied at Southport School of Art with Frank Hampson.

He joined Hampson's studio working on 'Dan Dare' for the 'Eagle', specializing in airbrush work.

He was sacked during the second story-line for objecting to the long work hours Hampson demanded, and worked in advertising for a couple of years before returning in 1955, and worked for Hampson alongside Don Harley and Joan Porter, until the studio was disbanded in 1959, after Odhams Press took over the paper.

After that he wrote scripts for the strip, with the infamous Frank Bellamy and Don Harley drawing for the first year, and Don Harley and Bruce Cornwell after that.

He finally left in 1962 and returned to drawing at TV21, working on "Lady Penelope", "XL5" and "The Daleks" among other strips.

He died at his home in Clun, Shropshire, in 1983, aged only 59.

Don Harley

|

| Don Harley Posing |

|

| Don Harley Posing |

Harley soon applied for and got a job in Hampson's studio.

He was the backbone of the strip, especially during Hampson's periods of illness, and worked with Hampson, Eric Eden and Joan Porter until the studio was disbanded in 1959 after Odhams Press took over the paper.

In the early days - when photographic reference featured strongly in the production of the strip, Harley would regularly pose as Digby, as his shape and figure were very similar ti the little batman.

He remained on the strip for a time, drawing the second page, while Frank Bellamy did the first, from scripts by Eden.

After a year Bellamy was forced to leave the strip (much to the relief of many of Dan Dare's devoted fans), and Harley became the lead artist, assisted by Bruce Cornwell, until 1962 when a new team of writer David Motton and artist Keith Watson took over.

He later drew "Thunderbirds" in Countdown (1971-72), and worked in nursery comics in the 1980s.

Bruce Cornwell

|

| Bruce Cornwell |

Bruce was born in Canada, but the family relocated to California, in October 1923 where Arthur Cornwell became a naturalized citizen in 1924 and worked for the film industry.

A second son, John, was born in California in 1927.

After growing up in Long Beach and Culver City, Bruce Cornwell came to England at the age of 15, accompanying his father who worked in the mid-1930s as an assistant art director for London Film Studios at Denham Studio, Buckinghamshire.

Bruce Cornwell studied art at Regent Street Polytechnic in London and the Académie Julian in Paris.

As an American citizen, he was not called up during the war but joined the Merchant Navy, transporting supplies to beleaguered Britain in U-Boat infested waters.

After the war, Cornwell established himself as a technical and general illustrator, working for women's and engineering magazines.

However, the wartime paper shortage had forced magazines to slim down considerably and Cornwell, who had married Peggy Brenda Huggins in 1941, and had a young son, sought out regular work, responding to an advertisement in a trade paper.

A badly printed reply outlining the duties came from Southport; unimpressed, Cornwell consigned the form to the bin.

A few days later he received an irate phone call from the Reverend Marcus Morris asking why he had not replied.

Bruce sent over some samples and was offered a job.

He made his way to Churchtown, Southport, and found himself working in a corrugated lean-to known as 'The Bakehouse', which he would later describe as "a hell-hole".

The team assembled by Frank Hampson was working flat-out to complete the early episodes of Dan Dare and Cornwell's talent for technical drawing meant he was usually called upon to draw the strips spaceships which filled the early episodes.

The team assembled by Frank Hampson was working flat-out to complete the early episodes of Dan Dare and Cornwell's talent for technical drawing meant he was usually called upon to draw the strips spaceships which filled the early episodes.

After only a few months Cornwell left: "Frank started questioning my technical skills and that was where I dug my heels in ... Even moving us to a room over a pub down the street didn't ease the situation. We were sacked. I was pleased, as the prospect of putting up with that programme for an indefinite period filled me with horror !"

To ease pressure, Hampson and his team were moved to Epsom and Cornwell was invited to rejoin, promising that things would improve.

"In the end I gave in. But it was the same as before; crazy hours, no time off and a massive work load.

To ease pressure, Hampson and his team were moved to Epsom and Cornwell was invited to rejoin, promising that things would improve.

"In the end I gave in. But it was the same as before; crazy hours, no time off and a massive work load.

Eventually, the hours, travelling and stress of the whole thing was too much and I became ill. My doctor told me to have a rest and I asked Frank for some holiday time. His reply was that he was ill too, and if he couldn't have time off, I couldn't either. I went back home that night and didn't come back."

On his return from holiday, Cornwell discovered a letter had been delivered telling him that he was fired.

Following Hampson's departure from 'Dan Dare', Cornwell was tempted back to assist Don Harley on the strip.

In recent years he had produced a number of illustrations for the excellent Dan Dare magazine 'Spaceship Away !'.

Sadly, Bruce died on 2 March 2012.

Greta, Don, Eric, Joan and the rest of the 'gang' to follow.....

No comments:

Post a Comment